The Mountain Mamaw is a complicated archetype. Typically, female characters who fall into this category are portrayed as strong, caring, hardworking, knowledgeable, wise, loving, and faithful.

Often they serve as the powerful matriarchs in their families and communities, giving friends, neighbors, and extended family members advice, food, aid, and more.

They may also be the keepers of various traditional knowledge (planting, harvesting, preserving food, traditional foodways, midwifery, caring for animals/other people in the community, well witching, faith healing, etc.).

Often, they are portrayed as being single, as well. Mamaws may also have their own style, eschewing modern fashion for the garments of yesteryear, and the archetype itself may or may not connote the age of the person.

This stereotype can sometimes intersect with the holy roller archetype.

The English Oxford Dictionary defines the term "holy roller" as a derogatory term meaning, "A member of an evangelical Christian group which expresses religious fervor by frenzied excitement or trances."

In the media, Appalachian women are often portrayed as being holy rollers (evangelical, holiness, or Pentecostal protestant Christians) who are consumed with religious conviction, sometimes to the point of fervor and/or cultish behavior.

At times, these women may or may not also be shown to be serpent handlers (which account for a very small population of mountain believers).

Such portrayals often do not show how faith/belief can be empowering for women in some contexts. It also leaves out those women from the region who may come from a different faith tradition (or lack of a faith tradition) altogether.

The holy roller may or may not intersect with the mountain mamaw archetype.

Appalachian Women (and men) are often portrayed as being drug addicts and/or having substance abuse issues.

Often, these representations do not take into account that the issue of drug abuse and addiction is one that can be found everywhere in the United States and beyond.

These portrayals also do not take into account other potential issues in a region like the mountains (mental health, poverty, lack of employment, lack of opportunity, etc.).

Typically, such stories portray addiction as something that should be looked down upon, instead of something that should be treated.

The drug addict may or may not intersect with the freeloader stereotype.

Which one is it?

The Appalachian woman is very often portrayed as being completely sexually available to men (even desperate for sexual contact and/or more likely to give into animal instincts), or they are portrayed as being totally sexually unavailable to anyone.

When being sexually available, they may be portrayed as being very attractive, dangerous, and may or may not be dressed in a provocative way (think Daisy Duke).

When they are not sexually available, Appalachian women are often portrayed as prudes or shrews.

Never fear, though... often times even these independent, fierce women may be tamed by a male partner who is willing to "rescue" or "save" her.

Who is the freeloader?

Often, this is a woman (who may or may not be single) who takes advantage of copious amounts of governmental assistance. As do her children, her partner, extended family members, etc.

They may get Medicaid, unemployment, disability, free lunch, etc. etc., all this provided by the American taxpayer and/or nongovernmental organizations.

Unlike the welfare queen, who also exists in Appalachia (usually in more urban centers), the freeloader is most often depicted as being entirely rural and (typically) white.

As such, there might be a strange juxtaposition between being prideful, and being from "strong" Anglo-Saxon or European stock, but also taking advantage of lots of public assistance.

Unlike the welfare queen, here, the freeloader is seen as still having a sense of pride that their whiteness allows them to have.

When, as a young child, I would totter into my grandparent's ridgetop house in Lee County, Kentucky, I can recall that my mamaw would almost always greet us by saying, "Hidy, hidy."

I can recall, as familiar to me as the curves in the road that snaked between my grandparents' home and my own, the words I said to my other family members on a near daily basis that, for the most part, I now use much more sparingly.

Words like "you'uns (collective plural)," "young'uns (children)," "squallin' (crying or screaming or speaking/singing loudly)," "idee (idea)," "packin' (carrying something from one place to another)," "yonder (over there)," "quare (not quite right or strange)" "puny (small or ill)," "holler (valley between two mountain ridges. Can also mean to yell or to contact someone)," "crooker'd (sideways or curvy)," "warsh (the act of washing, bathing, or a term for laundry)," "mess (a plethora)," "ruirnt (ruined. Also, used to mean drunk or spoiled)," "hind-end (bottom/backside/end of something) and also "hidy."

I have stopped using these words as often as I did while living in Lee County because I understand that as long as I hide my accent to a certain degree, or do not mark myself by using these words around certain people/at certain times, I can avoid judgement from others to a degree in terms of my background, where I come from, and certain offensive assumptions about that place.

To be honest, at this point in my life, I do this automatically, often without my even realizing it, to avoid scrutiny.

I understand all too well that when I open my mouth to speak, because of my accent, certain negative connotations or stereotypes may pop into the minds of listeners.

Recently, a friend of mine asked me to list off all the negative stereotypes that I felt like were closely associated with my own accent or an accent like mine. Here are a few of the things that I rattled off: Rural; White; Ignorant; Uneducated; Impoverished; Possibly racist, homophobic, or misogynistic (or all three); Possibly politically conservative; Possibly evangelical Christian; Possibly involved in incestuous relationships; Possibly barefoot (and/or pregnant); Possibly living in a trailer; Possibly living on welfare; Possibly a drug addict.

For some people, namely those living in the region and studying the area, the dialogue about stereotypes and archetypes is an old one. We've heard it all before. Both positive and negative. We are quaint, exotic, strong, and patriotic in one breath, racist, dangerous, and no-count in the other. As tired as it can sometimes seem, this conversation is still one that is important to have. Both with people outside of the region, as well as with one another.

Even more importantly, I would argue, we must engage in this dialogue on an individual basis, no matter where we are from or who we are.

This conversation really seriously began within myself a few years ago as I pursued a degree in Appalachian Studies from Berea College. Often, I found that many of the archetypes listed above showed up in a variety of writings, from local color coverage in the 1800s to novels, newspaper articles, and even country music songs.

As I began archival research as part of the Hillbilly: Appalachia in Film and Media team, I, again, saw many of these same archetypes appear in music, comedy sketches, movies, TV shows, comics, illustrations, etc. I noted that many entertainers from or of the region took these stereotypes on in order to appeal to a wider audience (take, for example, Grandpa Jones, Dolly Parton, or Stringbean).

Others worked to actively combat stereotypes or archetypes, creating media to challenge such notions (such as in the work of various film makers at Appalshop).

Still others are busy exploiting these archetypes in the form of reality television (Moonshiners, Appalachian Outlaws, and Snake Salvation), movies, the news, or television shows.

By learning more about these archetypes (both the negative and the positive), how they had been used by various entertainers and media makers throughout the years, and coming to understand how we can fight them by showing people just why they are inaccurate.

But why are they inaccurate? Is it because everything about them is untrue? Well, no. This, too, was something I had to come to terms with in light of my own experience as an Appalachian woman.

So often, our lives may have a great deal in common with any one of these worn-out stereotypes and archetypes. We might find ourselves on public assistance (like The Welfare Queen), or experimenting with substances (The Drug Addict), playing up our accent in hopes of attracting a partner (The Sex Pot), or serving as a keeper of traditional knowledge for our family members (The Mountain Mamaw).

Or, in my case, you might find that, for just a few years of your life, you played into the Holy Roller stereotype by being at the church house every time the door was open, singing with your family members as part of a gospel band, rebuking secular music, and reading The Bible in its entirety several times over.

The point is, though, that I am not only that archetype (even when I was having that experience in my life). So many times when these characters are used they appear flat. They are simply that thing, rarely portrayed as dynamic, complicated, or rounded in character. What we must understand is that all humans are human beings, no matter their circumstances, where they come from, or where they have been.

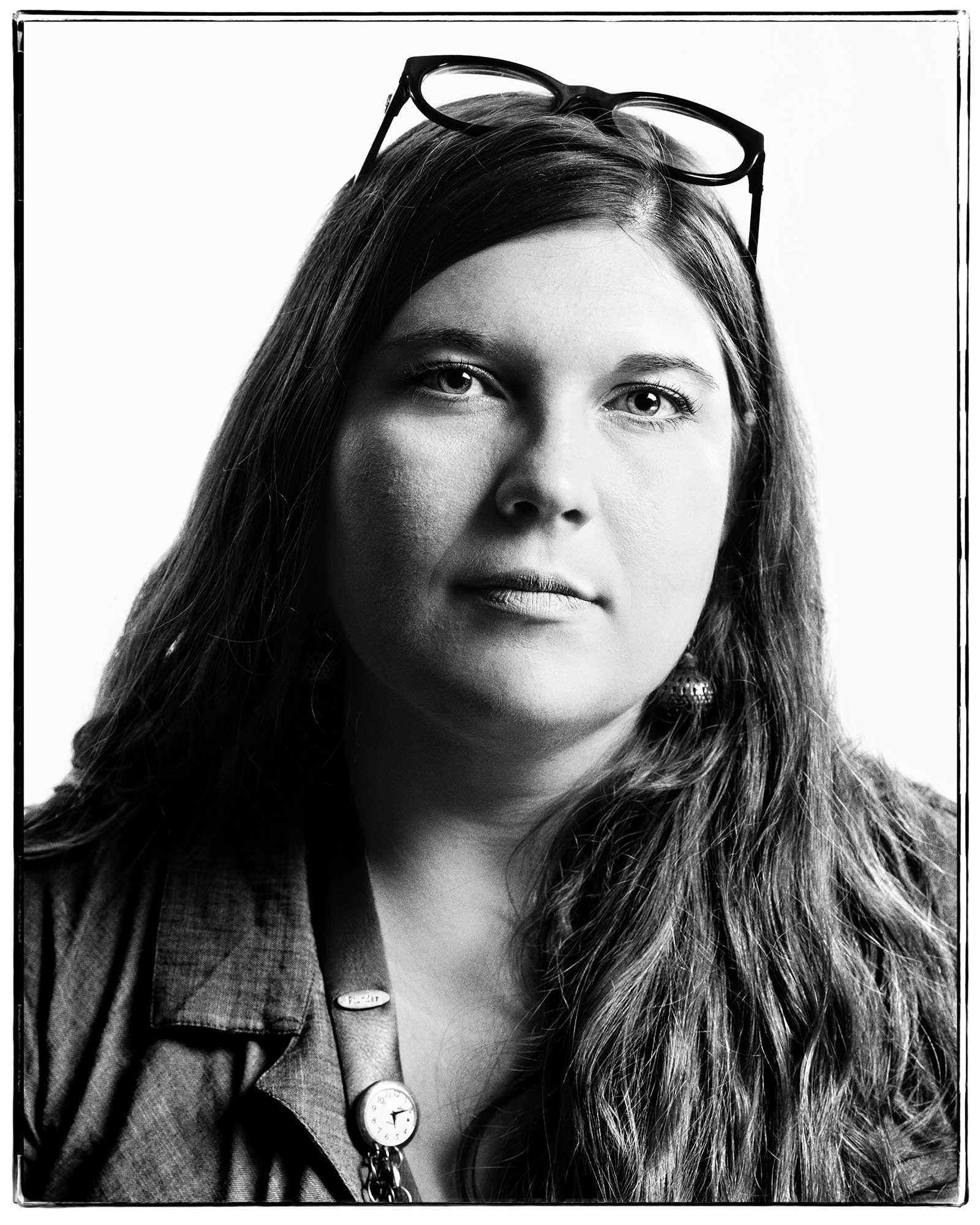

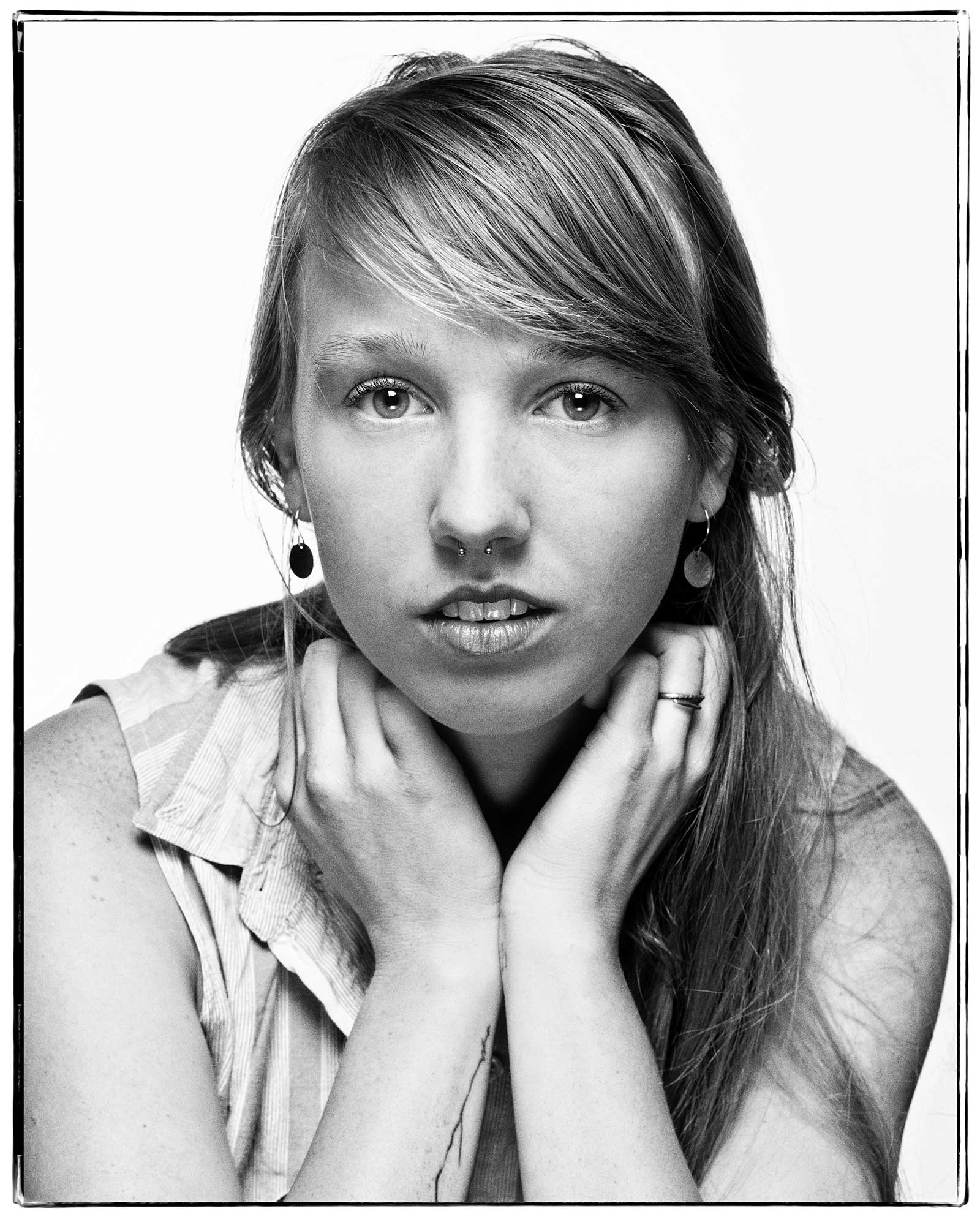

Everyone will always possess a depth and complexity that we cannot see from the outside, looking in. In each portrait on this site, the project team and I have worked to showcase this depth by speaking with people who are in and of the Appalachian region about how these archetypes may or may not relate to their lives, and showcasing both the intersections and differences in such a way that gives a much fuller picture of the individual, their background and backstory, and who they are as a person.

My hope for this project is that it will, ultimately, get others to question the validity of these archetypes and their usage in the media by getting people to think critically about portraying people as what are essentially "cardboard cutouts" of human beings.

Just in case you have not ever thought about it, I think the message here is pretty clear: There ain't nobody that flat, that glossy, that stiff, or that still.

Hopefully, if we can question the usage of media archetypes for one specific group (that of Appalachian women, in this case) that experience will later lead us to question the usage of stereotypes or archetypes for any group whenever they show-up in various forms of media, whether that be in the news, photography, music, on TV, or in films.

I hope that you enjoy each of these portraits!

I've been consuming images since I was young. My mother allowed me the guilty pleasure of sitting with magazines and leafing through them without constraint. I looked through catalogs, Life magazine, National Geographic, Sports Illustrated (even the swimsuit edition), and women's magazines (Vogue and Harper's Bazaar). My sister and I would sit together and name what we coveted. I would tear out pages and tape them to my walls.

In 1990, my first year in college, I was interested in the arts but felt I lacked skill as a visual artist of any sort. Before completely abandoning the notion of visual communication, I signed-up for a Black and White photography class. The evening of the first session the teacher entered the room with wild hair and piercing eyes, wearing a fatigue jacket, telling stories of projects overseas. I hadn't even shot my first roll of film, and I knew I was in the right place.

Between my first and last year of college, I transferred from school in West Virginia to a college in New England. At my new college, I was given the task of working on a year-long project as a senior thesis. I once again found myself pouring over magazines, specifically women's magazines from the 20th-Century. In the tradition of my grandmother's handicraft (she knitted, crocheted, cross-stitched), I spent hours cutting out figures and scenes and then reconstructing them into collages. Photoshop was just emerging, but my work was analog (film, paper, scissors, and glue). Thematically, the project strove to challenge the male gaze by reconstructing these scenes in a new way, from my perspective.

I remember this project as I survey what I created for Her Appalachia: collages about women. This time, though, it's digital. The collages include portraits created in a makeshift studio at Appalshop. I've layered these images with photographs and scans I took while visiting each woman's home. In some cases, I've added text from interviews conducted by Sam Cole and Lou Murrey.

My first job after college was teaching photography in a post-industrial town with a large Puerto Rican population. I worked at an after-school program for teens, showing them how to roll film, use cameras, develop their work (the old-fashioned way), and showcase it. The photography portion of the program had been started by a fellow alum who realized the power of placing media representation in the hands of the people.

When Sally Rubin, co-director of hillbilly, asked me to work on this project, I replied with an emphatic 'yes'. Her Appalachia gives me a chance to participate in the visual narrative of my home. In addition, through the research for this project, I learned about media archetypes of women in the region (none of which I identify with, nor do I see in those featured here). I hope what emerges from each of the collages is a picture of collaboration between myself and the subject. I hope the aesthetics call attention to our connection with past generations, the land itself, and to the rich history of Appalachian storytelling.

While I feel those involved in this project do not fit any media archetype of regional women, I continue to confront doubt in my work and ability that I believe stems from, one, being female, and two, being immersed in a narrative that portrays Appalachians as less than. This project, which allowed me to connect face-to-face, share commonalities, and become privy to differences, provided a step toward breaking through my own doubt. As I look into the faces of my fellow Appalachian women and our work, concepts of inferiority are shattered. Beauty, strength, and solidarity emerge.

Growing up, I knew I lived in Appalachia, but I didn't know I was Appalachian.

I knew that the mountains that rose up around my home in the northwestern corner of North Carolina ran so deep through me that their ridges built my backbone, and I knew that driving through the belly of East River Mountain into West Virginia for the Noel family reunion felt like homecoming.

But I didn't know I was Appalachian until my mama went back to school and a professor told her we were Appalachian on account of the fact that we were from Appalachia.

I didn't know I was Appalachian because since the turn of the 20th-century there has been a popular media narrative about our region, primarily determined by outsiders, that depicts Appalachia as an isolated land of poverty, backwardness, whiteness, fierce religiosity, and tradition.

It's a romanticized story that has established a rigid set of criteria for what it looks like to be Appalachian, and has denied many people a sense of belonging to the area... I am one of those people.

I am a queer femme photographer and community organizer from Boone, North Carolina, currently living in Knoxville, Tennessee.

I didn't know I was Appalachian like I didn't know I was queer, like I didn't know it was possible to occupy multiple identities or to find something like wholeness at their intersections.

Her Appalachia felt like an important project to be a part of because it turns out there are only so many times that you are told to leave or your story is erased from the narrative before you start believing your story never belonged here in the first place.

So when Sam asked me to be a creative consultant for Her Appalachia, I jumped at the opportunity to work on a project made by women in Appalachia that would center on the voices of women in our region.

Having media made by people, particularly women, from the region interrupts a narrative about what it looks like to be "Appalachian" and makes space to hold that we are "Appalachian enough" in the wholeness of our intersecting identities.

Sam Cole is a proud native of Lee County, Kentucky, where she was raised in a large, extended, mountain family.

While a student at Berea College, she majored in Appalachian Studies (specifically regional literature), and worked for the College's literary magazine, Appalachian Heritage. Sam now works at her alma mater providing staff support for one of the six Academic Divisions, as well as for the Dean of Curriculum & Student Learning.

Writing is a very important part of Sam's life. She has had poems and stories published in several regional magazines and anthologies. She writes about topics including modern mountain life, working class struggles, and gender issues. Sam enjoys reading, discovering new music and films, spending time outdoors, and getting in quality kitchen time whenever possible.

Sally Rubin is an adviser on Her Appalachia, as well as a documentary filmmaker and editor who has worked in the field for more than fifteen years.

Sally's film Life on the Line, a documentary about a teenage girl living on the border of the US and Mexico, premiered at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival in 2014 and was also broadcast across the country on PBS.

Her feature-length documentary, Deep Down (co-directed by Jen Gilomen), was part of the 2010-2011 Emmy-winning PBS series Independent Lens, and reached almost 1.5 million people through its broadcast, distribution, and outreach campaign. It was nominated for an Emmy for its Virtual Mine outreach project, in the category of New Approaches to News and Documentary.

The San Francisco-based Straight Outta Grrrlville Film Festival was founded by Sally in 2004 and continues to produce local events and benefits for artists and filmmakers.

Sally spent many of her childhood years visiting family and friends in the Smoky Mountains. A graduate of the M.A. program in Documentary at Stanford University, Sally currently resides in Los Angeles, and is a full-time documentary professor at Chapman University.

Ashley York is an adviser on Her Appalachia, and a filmmaker whose interests include feminist media, cinematic journalism, and media for social change.

She was featured in Variety as a "filmmaker to watch" and has worked on Academy Award®-winning teams and on projects that have premiered at the Sundance, Berlin, and SXSW film festivals, as well as on Netflix, A&E, National Geographic, IFC, HBO, and the Sundance Channel.

She co-directed and produced Tig, a Netflix Original documentary that premiered at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival, Hot Docs Canadian International Festival, Outfest, and the International Documentary Festival of Amsterdam. She is a frequent invited speaker, panelist, and contributor to Women in Film, the Southern Documentary Fund, SXSW Interactive, and the Sheffield International Documentary Festival.

Ashley is a founding member of the design collective, Take Action Games, which has partnered with the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality, ITVS, and the Center for Asian American Media. She was born in Kentucky and lives in Los Angeles where she teaches in the University of Southern California's School of Cinematic Arts.

Rebecca Kiger is a documentary and portrait photographer currently living in West Virginia.

She studied photography, education and anti-racism work at Hampshire College and has a second degree in Spanish and Latin American studies from UMass Amherst. Rebecca's work has been published in Lens, the photography blog of the New York Times, Looking at Appalachia, West Virginia Public Broadcasting, the Ohio Valley Resource, and Huck magazine.

Her still photography work is a component of two upcoming Netflix films by Elaine McMillion Sheldon about the opioid crisis. Rebecca also has photography work in the upcoming documentary by Nancy Schwartzman about the Steubenville, Ohio rape case. She is currently working on a long-term documentary project about intergenerational trauma and her family's roots in Appalachian Ohio.

To see some of Rebecca's photography, click here to jump to Rebecca's website.

Lou Murrey is a photographer and community organizer from northwestern North Carolina.

They currently live in East Tennessee and work with communities around issues of clean water access, rural broadband expansion, energy efficiency and building new structures of democracy at the local level through the Knoxville City Council Movement.

Lou has nurtured a lifelong love of photography and has used that skill to document a diverse array of experiences in Appalachia.

They just recently stepped into the role of interim coordinator for the Stay Together Appalachian Youth Project.

To see some of Lou's photography, click here to jump to Lou's website.